Content Note: This article discusses students’ social media responses to sexual assaults on campus. There are no descriptions of the actual assaults, though I do touch on the lack of services available to survivors of sexual assault on university campuses.

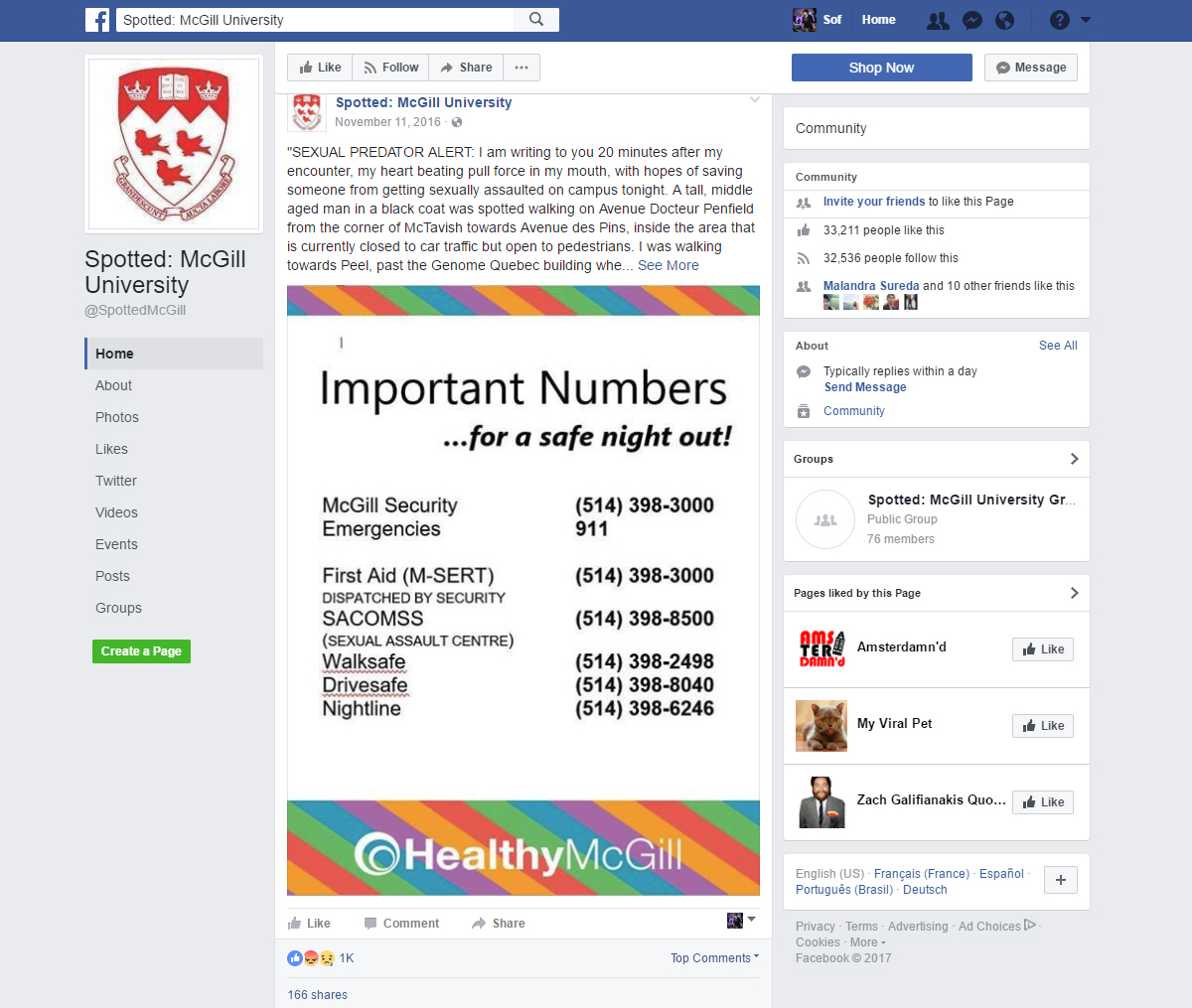

On November 11th, 2016, an anonymous graduate student posted a testimonial about their experience of sexual assault on Doctor Penfield Avenue, adjacent to McGill University’s downtown campus, on the Spotted: McGill University Facebook page.1 The post featured an image reminding students of McGill’s emergency phone numbers, and a detailed description of both the assault and the attacker. The post received over one thousand ‘likes,’ and was shared more than 150 times. A second post, detailing another assault likely committed by the same man, appeared three days later, as did a post containing information from a McGill security guard in response to the incident.23 The goal of these posts was visibility: to keep other students safe, and to bring attention to the often overlooked topic of sexual assault at McGill. Students achieved this end by co-opting a voyeuristic online space that provided them with the audience they needed.

This is not the first time social media has been used to spread awareness about rape culture, or respond collectively to the phenomenon. McGill Professor, Carrie Rentschler, has written about feminist responses to rape culture through online applications, like Hollaback!, describing the “affective space of response and support” such outlets provide, along with safety and prevention imperatives.4 The Spotted posts received dozens of students and community member comments offering safety tips, related stories, and messages of solidarity. This is all the more remarkable, because the Spotted Facebook page does not denote a feminist space. While the McGill page is fairly tame compared to other universities’ Spotted pages, which also invite posts about on-campus observations, it is still often used by male students to share unprompted comments about the appearance of female peers.5

They turned what was once a patriarchal tool for unwanted commentary on women’s bodies into an instrument for preventing further violation.

Thus, the students who shed light on McGill’s sexual assaults commandeered an otherwise voyeuristic platform. They turned what was once a patriarchal tool for unwanted commentary on women’s bodies into an instrument for preventing further violation. The Spotted page allowed these students to spread information rapidly. Scholars, like Jean Burgess, describe appropriation of online spaces for immediate use by communities in need, as ad hoc publics – she describes similar use of Twitter to organize aid initiatives during Hurricane Sandy.6 Professor Rentschler has also written about specifically feminist takeovers, or “media hijacks”, of Twitter hashtags. In one instance, she describes how hashtags are used to reproduce rape culture discourses.7 When the dissemination of information on a pertinent issue is urgent, any platform promoting visibility will do. While it is possible that the McGill students chose to share on the Spotted page because it offered access to their target audience, it may have also served as a last resort. Social media becomes the next best option, when no official channel exists for informing students of the exact nature and number of assaults on campus.

While other Canadian universities notify their students via email with detailed accounts of any violent crime committed on campus, McGill does not. In response to the Doctor Penfield assaults, students received one message from the University stating that the area would see increased security presence, but there was no description of what had occurred to prompt this action. Moreover, McGill had no institutional policy at the time to guide official response to sexual assault offences. The dialogue surrounding the sexual assaults reported on the Spotted group concluded on November 15, 2016 when the photo of a police officer escorting a man across campus appeared on the Facebook page with the caption “Stalker gets arrested.”8 Just eight days later, after more than a year of staunch student activism, the McGill senate approved an official “Policy against Sexual Violence”.9

The Facebook user who initially reported their assault thanked those who had circulated the post and provided supportive comments. She* posted on behalf of herself and another young woman who was also assaulted, writing, “I hope that our story brings our campus closer together and that we all have each other’s backs”.1011 It is impossible to determine whether these few Facebook posts influenced the prevention of other assaults on-campus, or led to the perpetrator’s capture, but their presence did play a significant role in spotlighting sexual assault and rape culture on McGill’s campus, and in providing a network of solidarity for survivors.

- Spotted: McGill University, “SEXUAL PREDATOR ALERT…” Facebook, 11 Nov 2016, accessed 19 Nov 2016.

- Spotted: McGill University, “Be careful on Penfield…” Facebook, 14 Nov 2016, (accessed 19 Nov 2016).

- Spotted: McGill University, “I just spoke with a security guard…” Facebook, 14 Nov 2016, (accessed 19 Nov 2016).

- Carrie Rentschler, “Rape Culture and the Feminist Politics of Social Media,” Girlhood Studies, 7.1 (2014), 77.

- Bates, L. “Facebook’s ‘Spotted’ pages: everyday sexism in universities for all to see.” The Guardian. 31 Jan 2014, (accessed 19 Nov 2016).

- Jean Burgess and Axel Bruns, “Twitter Hashtags from Ad Hoc to Calculated Publics,” Hashtag publics: the power and politics of discursive networks, (2015), 24.

- Carrie Rentschler, “#safetytipsforladies: Feminist Twitter Takedowns of Victim Blaming,” Feminist Media Studies, 15.2 (2015), 354.

- Spotted: McGill University, “Stalker gets arrested,” Facebook, 15 Nov 2016 (accessed 19 Nov 2016).

- Karen Seidman, “McGill’s new sexual assault policy gets unanimous approval,” Montreal Gazette, 24 Nov. 2016, (accessed 20 Feb 2017).

- I am assuming the anonymous author’s gender based on her reference to “another girl walking towards [her]” in the original post, indicating that she identifies as female.

- Spotted: McGill University, “I would like to thank all of you…” Facebook, 12 Nov 2016, (accessed 19 Nov 2016).

Show Comments (0)