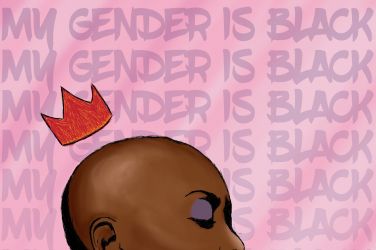

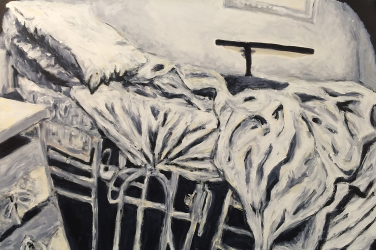

Image: farha najah, This painting was made for a March 2018 event, Celebrating Queer and Trans Muslims of Colour: Collective Arting as Resistance and Resilience.

I wanted to write something profound, something that would be meaningful and wise, something that would be helpful to others and that would validate the life I’ve lived so far. I wanted to write something so badly, it was crippling. Nothing would ever be good enough, wise enough, deep enough, which it turns out is exactly the point, hiding, as usual, in the whiskers above my lips. This is precisely the way a lifetime of having been wandered perpetuates its harm upon the body: self-replicating invalidation.

I always liked the saying “Not all who wander are lost.” For years I clung to it as a shield against the feeling of aimlessness that permeated my life. You see, mine is a tale of never fitting in, of always finding myself just outside of — disqualified from — the narratives society offers individuals to construct their identities. Born in California to Pakistani Muslim immigrant Canadians, the first time I was uprooted was before I was a year old, clear across a continent from a hot, dry desert to a cold, wet island. I grew up an anglo in Montreal’s West Island during the height of tensions between “Pure Laine” Quebec Nationalism and Canadian Multiculturalism, not realizing the general anti-immigrant sentiment of the Sovereignty Referendum and Bill 101 days would coalesce into the increasingly more precise Islamophobia of the last 17 years. Though my parents are culturally progressive for Pakistani Muslims and have assimilated with gusto to the North American way of life, my childhood in the 80s was one that was marked with a very early awareness that coming out as queer and genderqueer was punishable by ostracization, abandonment, and the guilt associated with being such an abomination it would “kill” my poor parents via shock and disappointment.

To this day I haven’t come out to my father because my mother continues to tell me he would die of a heart attack if he “found out”… an outcome made more plausible given he’s already had two in his life.

I’m outlining all of this partly because I believe there is a power in naming and sharing our experiences as folks with marginalized identities, and partly to highlight an experience with which I have become overly familiar:

As far back as I can remember, every aspect of my identity has been defined for me in terms of what I am not. Marginalization of identity is the shaping of the self by society through negatives. To borrow an art term, the self is created through negative space.

An example, from my own experience… in my life I have learned through the judgements of others that I am: not American enough, not Canadian enough, not Pakistani enough, not Quebecois enough, not Montreal enough, not Muslim enough, not Atheist enough, not skeptical enough, not spiritual enough, not son enough, not daughter enough, not man enough, not woman enough, not straight enough, not gay enough, not lesbian enough, not trans enough, not cis enough, not productive enough, not monogamous enough, not slutty enough, not worthy enough and not qualified enough.

Well, enough of that.

I feel blessed that in some small pockets of human civilization I have finally found words and concepts like non-binary, queer, polyamorous, and pansexual to define myself in an inclusive and affirmative way. Words that grew in small communities likewise forced into negative space, communities that pushed back and found the edges in the void and created something from the nothingness they were handed. Those of us who were wandered by society, excluded implicitly and explicitly through the weapons of social invalidation that are baked into the racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, ableist colonial profit-based hierarchical systems of human grading we all inherited. It is an amazing and wondrous thing to live a life during a time when this pyramid-scheme of misery and suffering is being called out and dismantled. To be present to watch the wandered find their way and come back to lead everyone else out of the darkness of ignorance and fear.

I don’t know if I’ll ever feel like I belong anywhere, or if I’ve been wandered too long to know how to feel anything else, doomed to always see the ways I don’t quite measure up. I suppose ultimately that’s why I’m writing this. This is the damage done by denying people the right to self-determine, of imposing rigid, narrow, exclusionary hierarchies of identity and belonging, of defining human rights as something that can be granted or revoked by the popular decision of people with so-called power: suffering. The suffering of never feeling whole and loved and valid. It’s an inhuman thing to condemn anyone to a lifetime of insecurity in the pursuit of your own comfort, the comfort of superiority and control. What kind of future do we build when the basis of a society becomes the building our own sense of invulnerability by inflicting destruction and invalidation on other human beings?

What kind of future do we build when the basis of a society becomes the building our own sense of invulnerability by inflicting destruction and invalidation on other human beings?

Somehow, we have lost sight that diversity has always been our strength, that the more ways people do their thing, the more ways our species finds of building tools to solve problems and continue the survival and well-being of not just our species but our planet. It is painfully obvious that the more specialized and homogenous a species, the more dependent it is on its environment staying static and the more easily it will fail to adapt and adjust to change. In our fear of the unknown we have created a society that destroys its own resilience to changing reality.

I don’t know why we insist on telling other people they’re not good enough. I now know that I have been good enough my whole life. So have you. We all have, and this piece of writing doesn’t have to live up to some imagined and arbitrary ideal any more than I do. We will both be exactly enough as we are for whatever our role in this chaos of a world is, no matter who or what else might try to invalidate us. We’ll still be here, and we’ll exist and stay wandered until it’s time to find home.

Show Comments (0)