Blank Noise is a community public art project dedicated to eradicating gender-based and sexual violence in India. Founded in 2003 by artist-activist Jasmeen Patheja, Blank Noise mobilizes members, called action sheroes, theyroes, or heroes, to create participatory campaigns that encourage social change and public safety for women and gender non-conforming people.

The following is a conversation between Jasmeen Patheja, and scholars Ayesha Vemuri (McGill) and Lakshmi Padmanabhan (Dartmouth).

Ayesha Vemuri: To begin, please could you both introduce yourselves and talk a little bit about your work.

Lakshmi Padmanabhan: I’m a postdoctoral researcher and faculty member at Dartmouth College. My PhD research explored the ways experimental video and photography by contemporary feminist artists from India respond to the women’s rights movement. I was interested in the ways that documentary pushes the bounds of what we think about as the work of photography and film in conjunction with feminist activism. In particular, I pursued an aesthetics of stillness, rest, and other forms of occupying public space that aren’t premised on performing the protesting subject.

Jasmeen Patheja: I’m an artist, who works with community and public arts. I facilitate Blank Noise, a collective that mobilizes action sheroes, heroes, or theyroes to take agency in dealing with sexual and gender-based violence. As an artist, I work with the community and design interventions for people—women, in particular—to confront fear and to feel empowered.

A: I’ll introduce myself as well. I’m a PhD student at McGill, working on climate change, infrastructure and feminism. In my Master’s work, I was interested in the question of transnational feminist solidarity building, focusing on how social media networks might help circulate knowledge from the global south and act as sites for building solidarities or not.

Could you say a little bit more about how you started Blank Noise, Jasmeen?

J: Blank Noise started in 2003 when I was in art school at the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology. I was new to Bangalore and it was my first time away from home. I was experiencing a lot of harassment on the streets and it’s not like I didn’t experience it growing up in Calcutta, but at least back then I had a safe place, a home, to run back to. Being on my own in a new city, experiencing constant harassment, hearing most people around me, most of my friends, say, “It’s something that happens. Get over it. Boys are like this,” created a sense of loneliness. I noticed that I was becoming very defensive on the streets all day. By that time, I had perfected the death stare… *laughs*

So I started questioning the potential that art carried with regard to harassment and safety. I became interested in performance art, community art, and public art. I wanted to explore how art could be made collectively, rather than by one artist, especially in relation to protest and healing. At school, I participated in a yearlong program that looked at the role of artists and designers in social transformation. It was really helpful to go through a process like that and to study the approaches of social movements and organizations, and the different tool kits they used to teach promote understanding. It was really eye opening to see just how complex it is to challenge a social issue. Communicating for social change has to be an iterative and integrative multimedia process.

I started questioning the potential that art carried with regard to harassment and safety. I became interested in performance art, community art, and public art. I wanted to explore how art could be made collectively, rather than by one artist, especially in relation to protest and healing. — Jasmeen Patheja

L: You started in response to the lived risk of the city. Would you say your approach to issues around women’s safety has changed in the last 10 to 15 years?

J: The nature of interventions designed by Blank Noise has been evolving. The starting point was rage, anger, loneliness, frustration. I learned to see the systemic in the personal and that continues as we build “I Never Ask For It,” a collective mission through which we collect “garment testimonies” from people, who share what they were wearing when they experienced sexual violence. Each garment is memory, witness and voice to someone’s experience. We are working towards 10,000 garment testimonials in 2023. For too long we were made to believe that personal incidents of violence were “one-offs” or isolated. Why is the word femicide used mostly in a single region of the world, when it refers to something that happens around the whole world?

But back to your question around how the interventions have changed—I’ve experienced a personal shift in understanding anger and in exploring questions of trust and fear. I’m still working through why I was taught, and so many women are taught, to fear all men until some prove themselves to be good men. Why is that the given? Questions guiding my art practice have been both personal, but have also been asked and answered through the collective.

A: I like what you said, Jasmeen, about moving from rage as the main focus, to now thinking about trust and vulnerability. It connects with your work, Lakshmi, and what it means to have a different kind of protesting body.

L: Yeah, I’ve been thinking a lot about the Blank Noise “Meet to Sleep” campaign and the conversations around it—from participants’ responses, to wider media coverage. I’m struck by the ways in which one can personalize the act of public occupation—using sleep or rest as the basis of an intervention, for example, rather than demanding a march where the measurement of success is the number of people that were there or the kind of media coverage that it got. “Meet to Sleep” asks us all to individually think about how we’re feeling in our bodies and how that sort of structural critique of risks from sexual violence, harassment, and patriarchy—all these big words and concepts that we use to describe the violence—how that’s actually lived and impacts our bodies.

J: I think that’s what “Meet to Sleep” really draws out—how each person’s experience of it is different. One action shero asked, “What stopped me from sleeping under a tree all my life?” and dared to question her right to rest. For another, it represented the right to be defenceless and free from fear. For others still, it means the right to leisure, or the right to be defenseless, or just to be in public space. There are so many different ways in which that one act can impact and really question both the person who’s participating, but also whoever comes upon that body. It does this sort of gentle act of recognition without saying what one needs to recognize.

For instance, I was really struck by the images that show some passersby who are looking at the sleeping body of a shero. There is a self-negotiation that happens while looking at that image. You have to ask, “Is this person judging the person on the ground? What am I thinking about this person who is doing the viewing?” Each image asks us to reflect on how we look at each other.

A: Sleeping is such a mundane act…

J: It’s fundamental.

A: Yes, it’s fundamental and brings you into confrontation with your own assumptions. Why do we perceive certain bodies as not belonging in the park, sleeping?

J: “Meet to Sleep” is an expression of our right to be defenseless, but when you open it up, anyone who participates does so because it’s saying something to them and that’s not something we can or want to control. It is rejecting every warning we have been made to internalise. It is stepping in, through experience, to say there is no such thing as “asking for it.”

We now have this visual representation of hundreds of women sleeping in parks across the country. What do those sleeping bodies say about women choosing to be defenseless rather than living in fear of being harmed and “being prepared” for harm? The right to be defenseless is an assertion and a desire and it is very much why we do “Meet to Sleep”.

We now have this visual representation of hundreds of women sleeping in parks across the country. What do those sleeping bodies say about women choosing to be defenseless rather than living in fear of being harmed and “being prepared” for harm? — Jasmeen Patheja

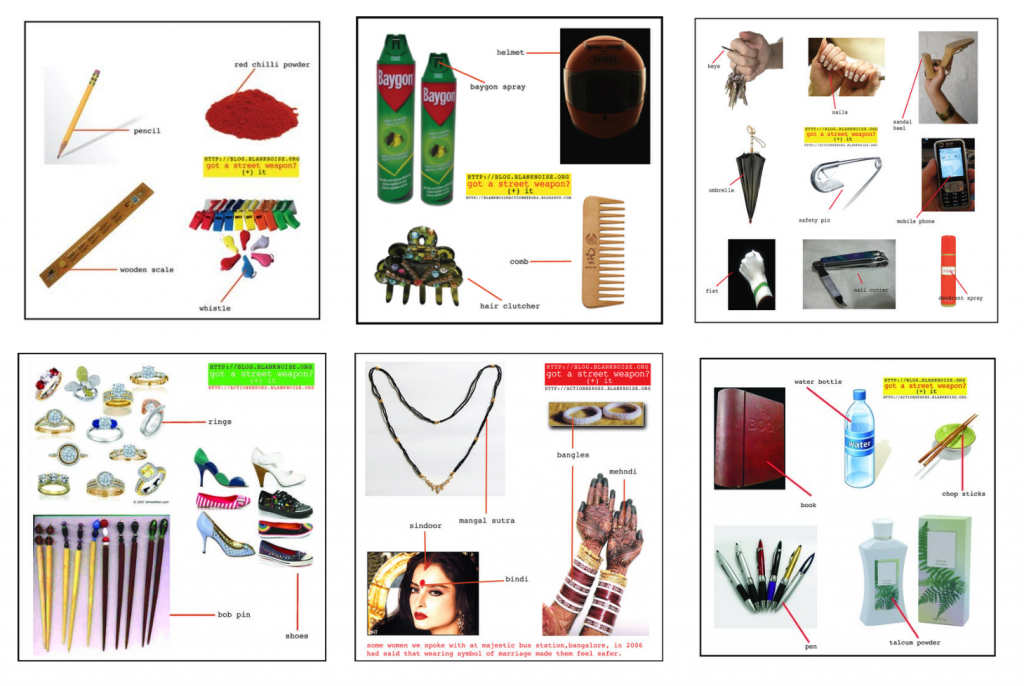

L: But you not only chronicle the right to be defenseless, but all the work it takes to be defended, or prepared for harm. I was really struck by your project “The museum of street weapons of defence,” which shows the kind of exhausting work undertaken every time women leave the house. They have to think whether they have chili powder or a pin or something to keep themselves safe.

J: Part of “Meet to Sleep” is to have the opportunity to unclench our fists, to be able to remove that fear that we carry on our shoulders. Ayesha, you mentioned “Talk to Me” earlier, which had a similar effect.

A: Yes, in “Talk to Me,” I definitely saw the sense of giving up fear; letting go internalized biases. You’ve said something before like, “there’s more intent to be fearful than there is intent to harm”. You said it better.

J: There are more of us in fear of each other, than with the actual intention to harm.

A: Exactly! That really resonated in “Talk to Me”, especially since it was published after Nirbhaya. At the time, there was so much public discourse about the migrant men who perpetrate harm. “Talk to Me” addressed that directly—the assumptions about who is a dangerous body and who is displacing whom—it asked us to reflect on our own complicity in systems of oppression. Is that something you’re thinking about? How we might overcome biases to create solidarity across difference?

J: I think that some things are shifting. Every project we’ve done has relied on the body of the “action shero” and her agency. We’ve used the internet, social media, and the press as a default partner to help spread the word. We want this to be a holistic conversation and to work more with allies. Besides “Talk to Me” and smaller group meetings, we want to create more spaces for men and women—I am cautious about binary gender division—but for men mostly to speak.

Because I’ve known some men who have been progressive and feminist—one man I know calls himself a “feminist-in-progress”. We want to create space for them to feel, explore, and articulate their thoughts. Some of them have been trolled on social media because of feminist decisions they’ve made, they’ve been bullied. We’ve had one project called, “A Very Deliberate Manel” that brought together 21 intergenerational men to speak in a nonjudgmental space. The last time we did it, we asked men, “Are you even aware that you’re seen as a threat just because you are in a body perceived as male?” It just became an invitation for men. Does that speak to your research?

L: I think there are many ways in which you frame what you want to do that resonate with the arguments I’ve been making in my research about which kinds of action address everyday violence.

I think there are multiple ways one can choose to make a political intervention and I’m interested in the ones that work on the mundane or the things that are felt, rather than seen. I appreciate that you affirm that you’re an artist, that you are trained as an artist, and that arts-based mediations can make change, as opposed to starting a political movement and then figuring out which artists can come and do PR.

I personally believe this is an extension of teaching or pedagogy. Gayatri Spivak says “pedagogy is the non coercive rearrangement of desire.” And that’s a very hard thing to do. We try to do it in our classrooms all the time, but oftentimes we completely fail at it, but that’s still the goal. If one person can leave the seminar room on feminist cinema, thinking about how images sort of shape our politics, that work is done for me. I see that your approach to your own work and practice also carries that power.

I think there are multiple ways one can choose to make a political intervention and I’m interested in the ones that work on the mundane or the things that are felt, rather than seen. I appreciate that you affirm that you’re an artist, that you are trained as an artist, and that arts-based mediations can make change… — Lakshmi Padmanabhan

A: I’m going to answer it more personally than from a research perspective. When I first came across Blank Noise, it made me think about just the everydayness of the fear we carry and the banality of patriarchal presence in my life all the time. While it takes work to undo it, Blank Noise gave me a vocabulary of deliberate, small acts through which I can fight back, like making eye contact or simply carrying myself differently.

I also really appreciate that you talk about learning from mistakes. That’s a direct lesson I can apply to my academic work—to admit that I may be wrong about something.

J: I don’t even see it as wrong or right. I just see it as an ongoing conversation. My understanding and knowledge come from listening to people and listening to how people feel when they bring their experiences and kind of community-led knowledge building wisdom building process. It’s iterative: one step leads to the next step. It’s a space of continuous learning. The fact that there’s now a space for queerness in Blank Noise came from an action shero who brought it up and said, “Hey, this is missing”. I had never asked about whether it should be about queer persons too.

A: As a closing question, I’d like to talk about all of the things that make Blank Noise more widely accessible to international audiences: the fact that it’s in English, it’s online and resonates with other well-known feminist movements, like Hollaback!, the Pink Chaddi Campaign (or Pink Underwear Campaign), and Take Back the Night. Hemangini Gupta argues that this is reflective of a new iteration of Indian feminism that is individualized and depends on a neoliberal feminist subject. Do you have anything to say about how some readings of your work focus on this individualized notion of change?

J: My understanding is that she was pushing an idea and creating space for debate, rather than saying this is exactly how it is and right. She was provoking another understanding for others to agree with it, or refute it. Rather than seeing it as her opinion on Blank Noise, I see it more as the work of an academic trying to make meaning and invite new meaning.

L: It’s something that I’ve been thinking a lot about and trying to write about in relation to “Meet to Sleep”. There’s an overwhelming critique from progressive academics about neoliberalization, which we can all agree is uniformly bad, but that doesn’t mean that everything that works at the level of the individual needs to be extrapolated into this neoliberal logic.

Before that, liberal logics were also individualizing, but even outside of that anti-colonial and civil disobedience strategies are about working on the individual in order to make a structural change. That sense of the place of an individual in a larger political structure didn’t come from neoliberalism and hopefully won’t die with it.

I think that there are other ways of recognizing selfhood, especially for people who aren’t allowed to or haven’t been told to ask themselves what they want or what they need. I was never asked what my desires were for myself, as a woman and as a sexual assault survivor who occupied all the places of privilege and loss that I have. I get a little bit frustrated with the distance that it sort of collapses anything individual to this failure of politics.

A: Thank you both so much for your time and generosity. What a great conversation!

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Show Comments (0)