Yuula Benivolski is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice centres photography, video, and installation. Twice displaced from countries she once called home, Benivolski grew up disconnected from her heritage until a distant cousin surprised her with a collection of letters handwritten by her great granduncle—a Jewish Trotskyist dissident writer imprisoned by the KGB—that offered tangible connection to her family’s past. In search of others who might relate to her story, Benivolski interviewed Jewish immigrants in Montreal from Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. Her resulting installation at the Museum of Jewish Montreal, titled “The Ocean Between Us,” explores notions of collective memory and identity through intimate portraits of her interviewees holding their most prized possessions—the objects that remind them of the loved ones who never made it across the ocean.

Sofia Misenheimer: Thank you for taking the time to speak with me today. As you may know, our current issue explores the many ways that art can offer a path toward healing in the face of pain and trauma. “The Ocean Between Us” seems to engage photography toward intergenerational healing for both you and your subjects. Could you tell me more about what inspired the project?

Yuula Benivolski: Most of my work is about personal histories since I didn’t always have access to my own. I was born in the USSR in 1980 but my family left when I was ten years old. At the time, life in the USSR was incredibly difficult with massive food shortages, violence, and corruption. The only way to leave was if you were Jewish and someone from Israel invited you. My father is Jewish and had a relative there, so we were eventually allowed to go, but it wasn’t an easy process. If you applied for an exit visa from the USSR, you might get one but oftentimes you wouldn’t be given permission to leave and instead would be punished by various government agencies and alienated by society. You would be fired from your job and no longer have access to any sort of social assistance or healthcare. People often ended up dying like that.

When we got our exit visas, my parents decided to leave right away. I remember getting ready to go to bed one night and my mom saying, “Actually we’re leaving right now.” They packed two duffel bags for our entire family [of five]: one outfit each, some books, and my parents’ guitar, which they would play all the time. That was it. No family photos, which was a big deal because my father was a photographer and we used to have a darkroom in our bathroom and wet prints hanging to dry all over the house. I don’t have any childhood photos, except for the one from my exit visa.

For a long time I felt like I had no access to my past. I had nothing tangible to remind me of it—everything was built on my memory and imagination. I couldn’t talk to any relatives easily or visit them, because we were stripped of our citizenship and our passports were taken away. When we left it was to never come back, all ties were severed. But as I got older, my need to know about our past became stronger. I started looking into our family history and I found out about my great granduncle Misha. His daughter is the one who invited us to Israel. One day I pestered her to tell me about her father, so she went away and came back with this stack of letters.

It’s just a mess of letters from different times. I started reading them and understanding that this was how they endured being apart. She left the USSR in 1970 and he wasn’t able to leave because he was on the KGB watch list until the day he died.

I realized these letters are the only thing I have linking me to some of our history and then I started thinking about other people with similar trajectories. My whole life I felt I was alone, but then I started thinking about the universality of that experience and wanted to hear from other people who were also denied access to their past, and to create a sort of past together by telling each other our stories, so we have something in common.

I wanted to hear from other people who also felt no sense of past and to create a sort of past together by telling each other stories, so we have something in common.

What sort of content is in the letters?

A lot of everyday stuff: “I went here,” “I did that,” which I think is very meaningful because it was a way for him to normalize his existence. He was someone very isolated, whose life was restricted, so the letters were definitely a lifeline. There was one, in particular, where the handwriting is very large because he’s addressing it to the KGB officer he knew would open it [to spy] and he says, “I’m writing this very clearly so that you can read it fast and send it to my daughter,” which is pretty funny. In another one he writes, “The comrades are looking after me,” to reference the KGB. They’re the sort of everyday letters of a person who’s stuck in one place and doesn’t want to be there.

Can you relate to that aspect of the letters? Is it fair to say that maybe “The Ocean Between Us” is not just referencing the letters or even the people you interviewed, but your own sort of embodied experience of immigration?

For sure. As an immigrant coming to Israel there was a hierarchy in terms of who was valued. There was bullying and open discrimination towards Russian immigrants. I used to pretend I wasn’t Russian. I lost my accent. I was discouraged from talking about Russian culture. It felt like something to be ashamed of. It was a strange feeling to completely cut myself off from anything related to my past. Then I moved to Canada and met Russian friends here who openly spoke Russian and it was like I could breathe freely again. I don’t know if it’s the same way now [in Israel], but the 90s were difficult. In my experience, Israel is a place that sustains hierarchies, and the participants change every couple of years. It’s a culture that appreciates power which puts you at a disadvantage if you are coming from a difficult place. So the project is about those internal negotiations you have to make when you are thrown into a completely new life.

Could you talk me through one of your interviews and how you engaged your artistic practice to weave together narratives and create a sense of collective memory and belonging?

There was this one woman who I especially connected with. She was nine years old when her family left Hungary. She told me how one morning when her mother was braiding her hair and getting her ready for school, suddenly they heard shots fired and the shots wouldn’t stop. She didn’t know it then, but it was the start of the Hungarian Revolution. Things quickly deteriorated for Jewish people in Hungary after that and they had to leave. She told me about taking a bus with her parents and their one suitcase to the border with Austria. They walked for something like nine hours with that suitcase and when they reached the border there were land mines everywhere, so they didn’t know what to do. Then they heard voices of people saying “Cross over here!” in Hungarian and they weren’t sure if someone was trying to trick them. But they took a chance and they crossed and realized it was another family on the other side who had already crossed and were trying to guide them.

After hearing her story, I asked her if I could take a photograph of her daughter braiding her hair. And when we were about to take it, she said, “I have to stop for a moment, I’m going to cry.” We took a moment, sat quietly, and then talked about the implications of these physical gestures that will forever remind us of trauma.

It was a difficult interview. This complete stranger who I’d never met before completely opened up to me. It made me feel like I’m not alone. I still think about her all the time.

This complete stranger who I’d never met before completely opened up to me. It made me feel like I’m not alone. I still think about her all the time.

So it seems to me that through your project there was the potential for healing and connection, but that in order to heal sometimes you sort of need to reopen an old wound?

Yes, for sure. You need to come apart and then bring it all back together. This happened for other people I talked to, especially other Russians. I told them my story and they told me theirs. We both talked about the pain of only bringing one thing from your old life—how you want to bring something that represents a core part of your identity. We discussed what we brought and why. I would tell them their experience is similar to every other person that I’ve met for this project and then they would start crying. They’re like, “Oh my God, I thought that was just me!”

Who would you say this installation is for?

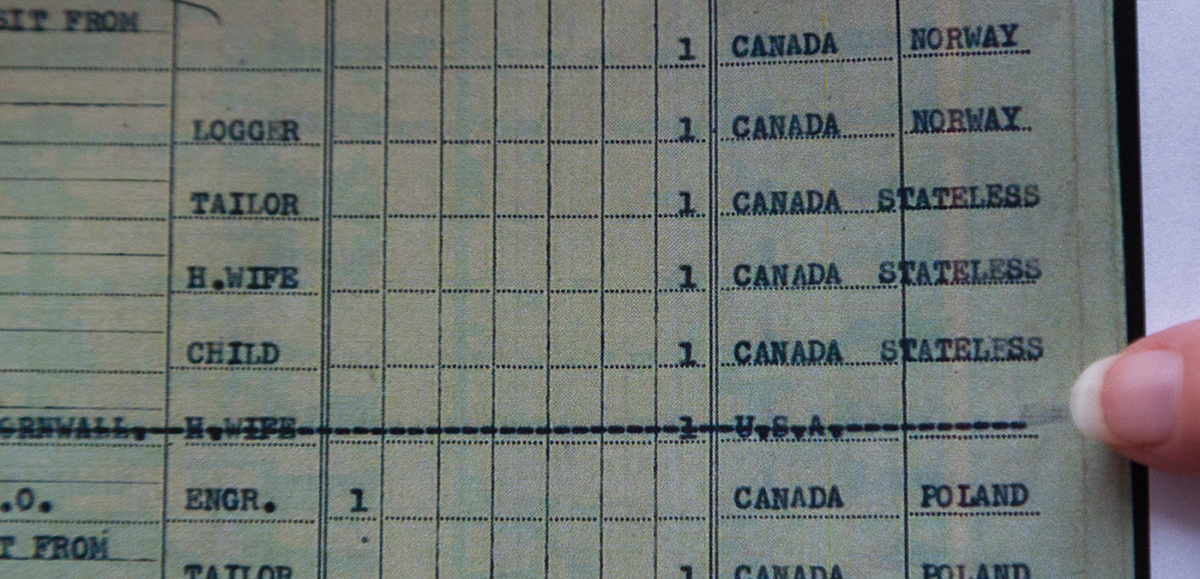

I made it for people like me. I don’t want to spoon-feed the viewer. If you went through a similar thing and can recognize the signs, you will know what this installation is about. For everyone else, it’s an intimate glimpse into what it means to be an immigrant or refugee. Some aspects of this experience are universal: whether for a passenger on the MS St. Louis, a displaced Palestinian family, or one of the many children affected by today’s refugee crisis. It’s important to remember these parallels and hear each other, especially now when so much work is being done to strengthen borders and keep people out. If someone can use my experience, or their own, to fight government efforts to shut people out—I want them to do it.

It was therapeutic to hear and record these stories. I don’t feel like I have a connection to any community that’s not my chosen community, or access to any cultural traditions that are emotionally nourishing. That’s a hard thing to realize when you get older since it can make life even emptier than it already feels as an immigrant. So I wanted to see if that connection can exist somehow – and it does. Despite all our differences, I feel like we really created our own collective history just by seeing each other and sharing these intimate details about our pasts.

“The Ocean Between Us” opens on Thursday January 31, 2019 at 19h00 with a vernissage that is free and open to the public. The installation will continue at the Museum of Jewish Montreal (4040 St Laurent Blvd) until May 5, 2019.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Show Comments (0)