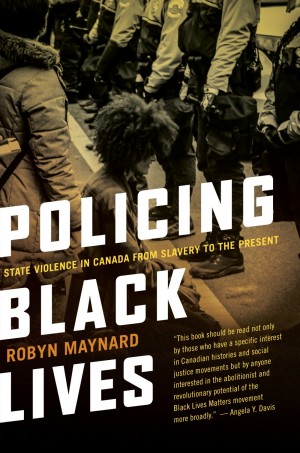

Robyn Maynard is an author, community organizer and educator based in Montréal. She has been a part of grassroots movements against racial profiling, police violence, and punitive detention and deportation practices for over a decade and has an extensive background in harm reduction and community work. Her expertise is regularly sought in local and national media outlets; she has presented before Senate committees and the United Nations, and made numerous presentations on anti-Black racism, gender, criminalization and the lasting legacy of slavery in Canada. Most recently, she is the author of Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present, (Fernwood 2017).

Vincent Mousseau: I’m sure that you’ll need no introduction to many of our readers, but would you provide a brief overview of the work that you do and your background?

Robyn Maynard: I’m the author of the book Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present, but that book was something that emerged out of my longer activist history. My writing has always been something that I’ve used as one part of the ways that I conceive of what it means to think about what it is to fight for social justice. I think one of the reasons I’m so focused on intersectionality in the book is my background in activism and harm-reduction work of all sorts over the past decade. I worked off and on with Head & Hands, a harm-reduction-based non-profit working with marginalized youth and drug users, many of whom were Black and/or LGBTQI. I later went on to do full-time outreach at Stella, an organization made mostly of current and former sex workers. I was also involved with migrant justice work with No One Is Illegal Montreal, and helped found a group called Justice for Victims of Police Killings, created in 2010 by Bridget Tolley, Julie Matson, Lillian Villanueva, and other family members who’d had their loved ones killed by the police, along with supporters. I’ve also been involved with many different grassroots groups working to fight racial profiling and police impunity, including Project X, a youth-oriented racial profiling/know your rights project based in N.D.G., and later on, Montreal Noir. Because I’ve spent a lot of my life working with people who were in and out of jail, sometimes using drugs or involved in sex work or other grey economy work, it’s been impossible not to see the harms of policing and criminalization, particularly as they impact the most marginalized people. And it’s still too rare, in Montreal in particular, that people name that it is disproportionately Black people who are facing poverty, who are being harassed and sometimes beaten by the police, whose loved ones are facing deportation or having their kids taken away. I’ve witnessed first hand so many instances of what can only be called state violence against Black folks, especially Black folks who are poor, living with precarious citizenship, LGBTQTI*, or involved in street-based economies. I wanted to find a way to address that with my writing, but also to provide a historical framework toward understanding all of this, that can be traced back to slavery.

I’m currently touring the book across Canada and across the United States, to bring it into the conversation, in terms of how we talk about anti-Blackness and what it means to say “Black Lives Matter” today in Canada.

Vincent: In a lot of ways, your book really challenges the status quo, particularly in the way that it challenges Canada’s moral superiority around issues of state violence and points out that it is not just a problem that happens in the United States. In fact, this book concretely proves the contrary. How have you found the reactions to that?

Robyn: In some ways, the reception has surprisingly been quite great. There has been so much brilliant work had been produced about addressing different kinds of anti-Blackness in Canada that I feel really should have been on the curriculum; things that should have been more widely known. There is some brilliant work that has just been invisiblized by the media and by the broader cultural landscape. At the same time, I think what is helpful and novel about my book is that it draws a line from slavery directly into so many of the issues facing Black communities today: disproportionate child removal, over-incarceration in jails and prisons, street-checks, police violence, and the school-to-prison pipeline.

I’m happy to have written a book that contributes to that conversation, but I wasn’t really expecting the response that it got. The fact that it has made the CBC bestseller list for multiple weeks – the fact that it’s getting out to places I never would have imagined – is great. I think that some of this stems from the fact we’ve seen increased visibility of Black activism in the last five years or so. The Black Lives Matter-Toronto occupation of the Toronto Police Service headquarters in Toronto, for example, has been so inspiring. Same goes for the work of the Abdirahman Abdi Coalition in Ottawa, as is the work of Black Lives Matter in Vancouver. I think that because we’re also seeing this national and international resurgence of Black resistance –and of Black feminist resistance – we are being put in a moment when many people are beginning more to ask questions about the realities of anti-blackness in Canada.

So in that way, I see the visibility my book has received as an affirmation of the successes of our movements – there have been so many Black activists, including BLM chapters, El Jones in Halifax, Blackspace in Winnipeg, who have made it difficult for the broader public to ignore the realities facing Black populations here. I think we are getting to a place that’s now harder to deny the legacy of Canada’s history of slavery, segregation, and anti-Black violence on the present. Something that’s been really great with the book tour has been going to places that have relatively small Black populations – I’m thinking Vancouver, or Kingston, or Kitchener –and doing book events that involve community discussions or presentations on local realities of anti-Blackness. It’s been incredible to learn about how anti-Blackness is experienced differently across the country, yet there are so many similarities no matter where we are, as well. As you mentioned, we as Black folks are often taught that our experiences aren’t valid; that we don’t experience racism here. It is always compared to the States, and that’s always used to as a way to dismiss us, to make us seem “crazy”.

For me, writing this book was a means to counter the way in which this narrative is often thrown back at us. I think that for many people reading it, it’s also an affirming moment to be able to say that, for example “Yes, the treatment that I experienced in school wasn’t an isolated incident”. I think that having a lot of the empirical information to back what many of us have experienced seems to be resonating for a lot of people.

Vincent: A recurring theme that I see a lot in your work is a commitment to bring marginalized groups to the forefront. So, whether it’s focusing on Black feminist scholarship, or on the relationships between Black and Indigenous communities, you always find a way to ensure that those voices are heard; always bringing in those intersectional connections. Why do you feel it’s important to highlight these voices?

Robyn: I think that it’s always important for us, whenever we can, to make sure that we’re really being attentive to the different ways that people are marginalized, and to commit to thinking about that marginalization in an intersectional way. In Canada, we’re already so coached to not even believe that racism exists. As a result, when racism is conceived of, it’s often thought about as this very classical experience – for example, the treatment of young Black men by police officers. That is, of course, something very important to focus on, as that’s a very significant reality of the Black experience in Canada. But I think that what often ends up going unseen are the many different kinds of harm that are being experienced by Black women, particularly by Black trans women, by gender nonconforming people, by folks that don’t conform to the heterosexual norm… There are so many different other ways that anti-Blackness actually compounds with these other kinds of marginalization, and we need to make these experiences central our fight against racism.

I think that it literally becomes too narrow for us to address, if we’re not conceiving that different ways in which Black people are experiences harm. Whether that’s because they’re undocumented, whether that’s because they have mental health issues, and so on.

Vincent: Your book has the ability to challenge people in the way that not a lot of books do. This book shakes the interpretation that people have of their country and vastly changes the way that they walk through the world as a Canadian citizen and forces them to question what that citizenship means. In the activist work that the both of us have been doing, we’ve seen that folks have a tendency to lash out when their views on something so intimate are challenged. I can only imagine the amount of vitriol that you’ve faced.

Robyn: I would say that I have, but I also really love the block function and the spam folder [laughs]. There’s definitely been that response of, “Go back to Africa”, or “You’re the real racist” style hate mail, or Twitter mentions, and things like that. Something that I’ve realized as I travel to tour this book is there’s something about the way that Canadians have been educated with a particular sort of national innocence. I think that this book does tend to shake people a little bit, but it also brings forwards this history that I realize that many people didn’t really know. For example, many Canadians didn’t even know that slavery existed here, and if they do, they know extremely little about the ways that Black men, women, and children were enslaved, beaten, and held in captivity. They often don’t see that as a part of that history. And the lack of knowledge around things like segregated schooling.

I think that people are often aware of issues like carding, but what I’ve been realizing is that there has been so much misinformation and erasure of the Black Canadian experience. I’m also finding a surprising level of interest in some places where I would have expected hostility, and that’s been a very interesting part of this as well.

The ability to have those kinds of conversations is inherently soul-nourishing for me; putting my work into conversation with people who have inspired me for so many years is something that fills my heart with a certain kind of love.

Vincent: I am not at all surprised that people are feeling profoundly touched by your work, and the perspectives that you bring to the forefront. As you know I do some work around organizing within Black communities in Montreal, trying to facilitate conversations about which Black lives “matter” in our discourse, with a particular focus on the intersections of different forms of marginalization. I often get a lot of folks saying, “wow, I didn’t think about it this way. I didn’t understand the way that misogyny, and homophobia and transphobia were creeping their ways into our movements.” And I’m glad that we were able to shift and address it. I imagine your book has probably had that transformative effect for a lot of people, as well.

Robyn: Yes, I like to think of this book as being, at its best, an educational tool. It is a book that does contain a lot of jarring information that people might have to process. I hope that this book creates the circumstances to jar people’s view of the country that they live in, and that country’s history. I was also trying to write it with love for Black people; to bring out the brilliant Black resistance that is so much a part of this history, and to highlight much of the great Black scholarship that has also been done on this issue. I hope that it was effective at bringing the diversity of Black lives to the forefront.

Vincent: I imagine that having a book tour on top of being a parent and an activist involved in numerous social justice causes is very draining. How do you make time for self-care?

Robyn: One of the things that has really nourished me in the last year – or at least since the book has come out – is the conversations that I have had the privilege to take part in. I’ve had the opportunity to meet many Black elders that I have a lot of respect for; people who have done brilliant work. Getting to meet and speak publicly with people like Dionne Brand, Angela Davis, and Joy James, for example. I’m going to be at an event with Leanne Simpson very soon. The ability to have those kinds of conversations is inherently soul-nourishing for me; putting my work into conversation with people who have inspired me for so many years is something that fills my heart with a certain kind of love.

Another thing that helps me get through is having the ability to meet a lot of older Black activists from across the country. These are people who have been doing incredible work for decades. Speaking to and realizing how far back we go – just how badass our people are – is something that’s been really, really incredible.

I do need to remind myself just to stop working at a certain time of day. While having a child in some ways adds a significant level of labour to your life, it also makes you slow down, stop, and be present. It’s the kind of thing that stops me from reading a report about racism from 5:00 to 9:00 PM, for example, because that’s when it’s time to give my son a bath, to have supper, and to do these very family-oriented things. In that way, I actually find my son Lamar extremely grounding for me, in the way that I am forced to just slow down and enjoy the interpersonal aspects of life.

The time around when I was finishing the book was really intense. As you remember, that’s when Bony Jean-Pierre was killed. It was a moment of renewed Black activism in Montreal. Trying to find the energy to spread the fight in so many ways at that moment was definitely exhausting and depleting at moments, I can’t pretend that it wasn’t. I do need to remember that in some ways, life is literally a constant state of emergency for Black folks. But I also need to remember need to not treat every day as an emergency, so that I can pace myself for the long haul.

Vincent: When we’re talking about issues of state violence, oppression, and other systemic forms of marginalization, we are often reunited by our trauma; I’m thinking about the ways in which many of us only see each other at vigils or rallies in support of Black lives. Despite this – or maybe because of this – I think about the ways that we can move towards thriving instead of merely surviving. A lot of which you said around the creation of community really speaks to me. Recognizing the strength that exists in our communities as something that is often born from trauma, but which somehow manages to create something so beautiful and so representative of our resiliency. And I think that’s a beautiful note to remember as we attempt to move forward, and as we – as Angela Davis put it – “attempt to lift as we climb.”

Show Comments (0)