Still from video by Aquiles Ascencion.

Lee-Ann Martin is an independent curator of Indigenous art and the recipient of the 2019 Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts for Outstanding Contribution. She is the former Curator of Contemporary Canadian Aboriginal Art at the Canadian Museum of History, and the former Head Curator of the MacKenzie Art Gallery. She was the Paul D. Fleck Fellow at the Banff Centre, where she coordinated the first Indigenous residency. She also served as the Coordinator for the Task Force on Museums and First Peoples, and she was the First Peoples Equity Coordinator at the Canada Council for the Arts. Lee-Ann has curated various projects that have been presented across Canada and toured abroad, including the 2018 national billboard exhibition Resilience, and the foundational 1992 exhibition at the Canadian Museum of Civilization, INDIGENA: Perspectives of Indigenous People on 500 Years.

Sofia Misenheimer: Thank you so much for speaking with me and congratulations on your recent award! Please could you tell me a little bit about your background and what drew you to your role as an independent curator?

Lee-Ann Martin: I grew up away from my reserve, Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, on the Bay of Quinte. In university in the 1970s, I wanted to take Indigenous art courses, but, sadly at that time, there were none offered. I had to take a combination of anthropology and European and South Pacific art courses.

In the mid-1980s, I was working at the University of Maine at Orono, when I heard the news about a large international exhibition of historical Indigenous artifacts, The Spirit Sings, being planned at the Glenbow Museum in conjunction with the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary. I became angry not only because there were no Indigenous curators on the exhibition’s curatorial committee, but also because the main exhibition sponsor was Shell Canada who were responsible for the ruination of the land and resources of the Lubicon Cree community in northern Alberta.

In an effort to become one Indigenous voice in the museum profession, I enrolled in a Masters in Museum Studies at the University of Toronto to research the issues that were prevalent at the time. I didn’t enter the field with the express wish to become a curator but rather to become an Indigenous representative in the museum world. However, curating found me.

I didn’t enter the field with the express wish to become a curator but rather to become an Indigenous representative in the museum world. However, curating found me.

How did that come about and what was the experience like?

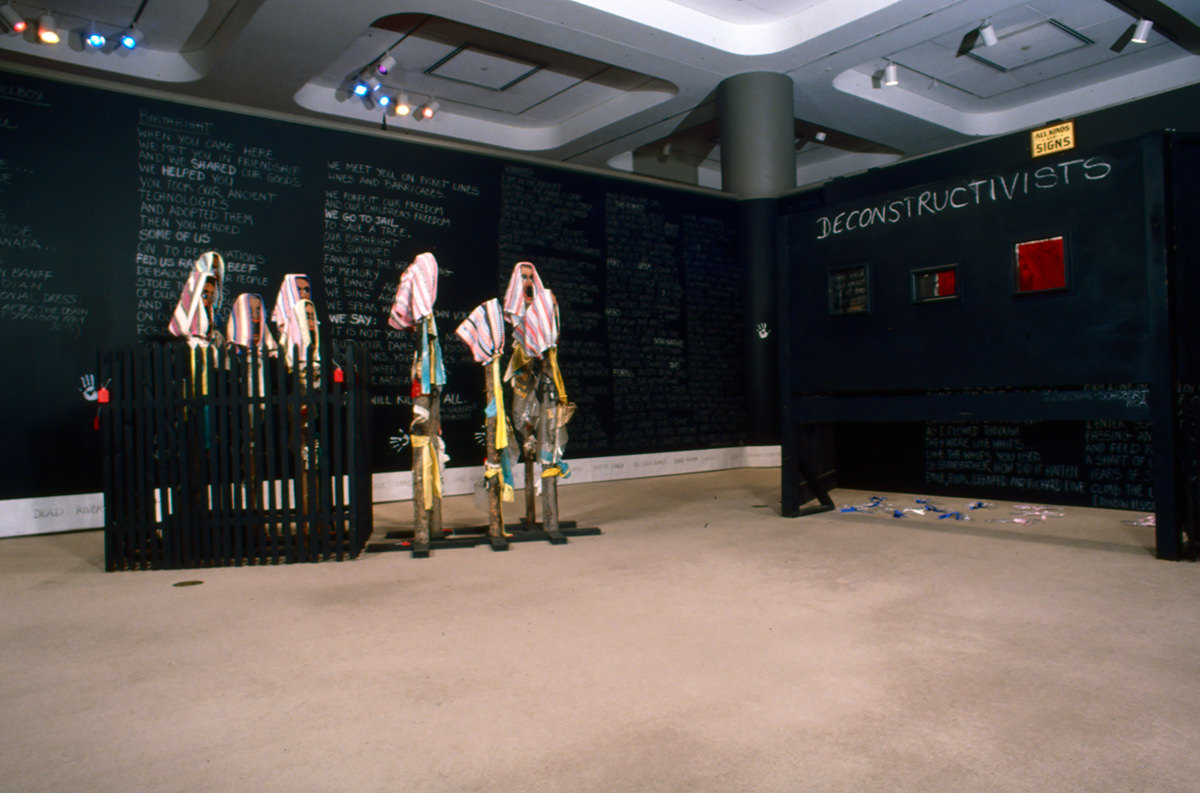

There was a selection committee to choose the candidate for the artistic/curatorial residency at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in 1989. For this interview, I proposed an exhibition of contemporary Indigenous art that critiqued the 500-year anniversary of the arrival of Columbus in the Americas, which became the exhibition, INDIGENA: Perspectives of Indigenous Peoples on the 500 Years.

I loved what the artists who participated in INDIGENA were doing, reclaiming their history visually and seeking out new ways to express their hopes for the future. It captured my imagination as a curator.

INDIGENA, which took place nearly 30 years ago, has been referred to as “a turning point in institutional recognition for Indigenous art”. What sort of response did you get to that project?

INDIGENA was a turning point for several reasons: the fact that two Indigenous curators curated this exhibition at a national museum and also that the subject matter was very political, critiquing the 500 years of colonialism. There was huge pushback from many non-Indigenous visitors to the museum who wanted to see “pretty” historic art. They weren’t ready or prepared for the kind of contemporary art we displayed. However, the Indigenous art community embraced it.

Self-representation features in a lot of your work. Your recent “Resilience” exhibition, for instance, foregrounded art by contemporary Indigenous women and advocated for cultural sovereignty. What sparked that project?

The artist-run centre, MAWA (Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art) in Winnipeg wanted to apply to the Canada Council’s one-time program, New Chapter, for an exceptional project beyond their normal activities. They had decided upon a national billboard project when Shawna Dempsey, co-executive director of MAWA, contacted me to ask if I would like to curate such a project, with the subject matter at my discretion. I was excited to work with MAWA and wanted to do an exhibition of Indigenous women’s art as, historically and until recently, Indigenous women’s art had been collected as anonymous objects or anthropological artifacts.

My intent was to show the diversity of artists—in the approaches to their art practices, in mediums selected and in stages in their careers. It is important to note that we disassociated the project from Canada 150 celebrations in 2017 by holding the projects the following year, June – August 2018.

I was excited to work with MAWA and wanted to do an exhibition of Indigenous women’s art as, historically and until recently, Indigenous women’s art had been collected as anonymous objects or anthropological artifacts.

I was wondering about the timing, that’s an effective tactic to decentre the “anniversary” narrative. Art/iculation actually emerged from an arts-based project aiming to make space for dialogue and encounter around anti-colonial concepts of place and agency, and to decentre dominant celebrations of colonialism during Montreal 375/Canada 150.

How did you go about selecting participating artists for Resilience?

I began the selection of artists and artworks with a few iconic images that were very familiar to many audiences, i.e. Shelley Niro’s, The Rebel, and Rebecca Belmore’s, Fringe. I consulted with colleagues and did further research into artists with whom I was not particularly familiar. Then, in conversation with them, via email or Skype, I selected the images. My main criterion for selecting the images at this point was that they have strong visual impact and fit well in the billboard format.

An important aspect of this project was for viewers to be surprised to see these images on a billboard and then to become curious about the artist and engaged in the project. For the curious viewer, we hoped that they would access the website to see all 50 images together, their locations and further information, such as my curatorial essay, The Resilient Body, and audience responses.

Did you have an intended audience in mind?

The intended audience was, very broadly speaking, the Canadian public – people who were travelling daily to and from work or school, people embarking on a summer road trip across the country. Because the artworks were outside art institutions, we hoped that project would engage audiences not necessarily familiar or comfortable with art institutions. During my research, I found an advertising survey from a few years ago that stated that, of all the advertising formats, billboards are the most effective for remembering their messages.

Did you craft a narrative thread through the pieces? Do you see your curatorial practice as a form of storytelling?

While I had no themes or narratives in mind when first selecting the works, as I considered the exhibition in total, a number of narratives appeared: the female, self-representation, Indigeni(city), the environment, traditional knowledges and practices, and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. I see my practice as more of a facilitator of the artists’ stories and the various connections among them. I always look for works in which the artist has succeeded in their mastery of materials and conceptual goals.

Since your initial project, INDIGENA, do you think the art landscape in Canada has changed?

When I first started, during the ground swell in late 80s and early 90s, I wanted to work myself out of a job by creating more opportunities for Indigenous curators and artists. Thirty years later, the art landscape has changed incredibly. There are now many Indigenous curators, exhibitions and works in collections of mainstream art museums. University programs in Indigenous arts now exist and most funding agencies, including the Canada Council, have targetted programs of support. It’s night and day from when I started.

A lot of your work looks toward Indigenous futures—what more would you like to see happen?

There are so many artists working through that, looking at the future. It’s a cyclical timeline and I think about the number of Indigenous scholars now who are transcending the Eurocentric academic frameworks. It’s about bringing the past into the future.

There are so many artists… looking at the future. It’s a cyclical timeline and I think about the number of Indigenous scholars now who are transcending the Eurocentric academic frameworks. It’s about bringing the past into the future.

Do you have anything currently in the works?

I have a few projects planned, including a book on Indigenous Women’s Art in Canada, inspired by Resilience and my own interest in this subject area.

What does it mean to you to have won the Governor General’s Award?

This is a wonderful recognition of my work and a perfect culmination of my career. It pleases me especially because of the respect shown to me by the two nominators, Richard Hill and Candice Hopkins. And to be selected by a jury of my peers is also very rewarding. I am humbled to join the many respected arts professionals who have received this award in previous years.

Congratulations again on your well-deserved recognition and thank you for sharing so generously about your work!

Show Comments (1)

Nnamdi Greeley

Thank you for this revealing interview, and for the wide range of dynamic reporting, expression and viewpoint presented in Art/iculation.

Our society urgently needs a magazine of this sort, and I have no doubt that more and more readers across the social spectrum of Canada and the U.S. will will be realizing this as they discover your marvelous publication. Congratulations on your success in bringing this about!